Will a woolly mammoth be cloned and placed in Siberia?

It has long been the desire of ecologists to clone a woolly mammoth, the icon of the Ice Age.1,2 The remnants of DNA in frozen mammoths are highly fragmented, so the only way forward would be to use an Asian elephant’s DNA to make up the missing bits. As we have explained elsewhere, this is highly unlikely to succeed.3 Also it would really be a hybrid of sorts, a ‘mammophant’, rather than an actual mammoth.1

The plan is to put such a ‘mammophant’ into Pleistocene Park in northeast Siberia. Pleistocene Park is an experiment to ‘rewild’ an area of 20 km2 (7½ sq. mi) in northeast Siberia with large mammals to change the wetland back into a grassland. It is hoped that the mammophant could withstand the cold of Siberia better than the Asian elephant.

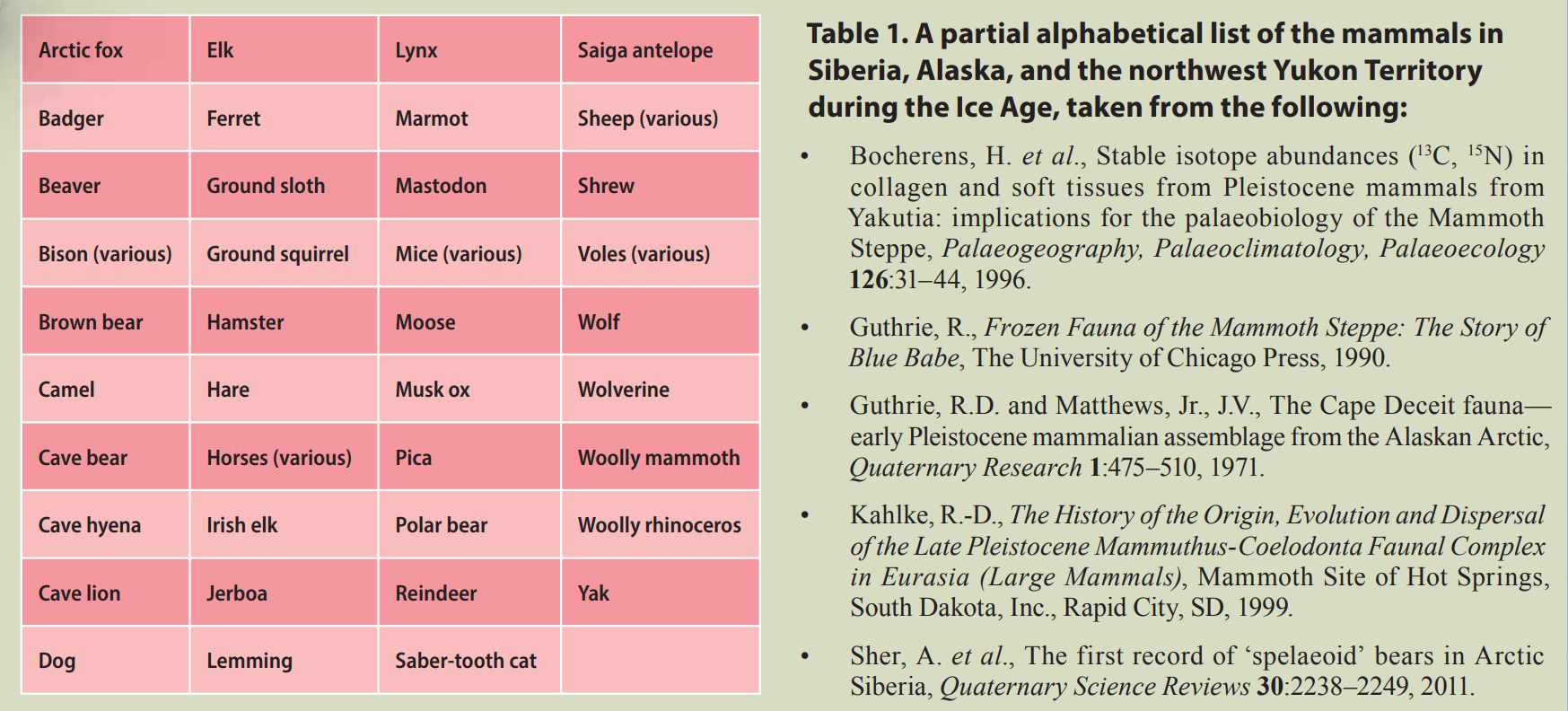

At least forty species of mammals lived in the non-glaciated Arctic during the Ice Age (table 1). The area is described as having been similar to Africa’s Serengeti.4 Today, many of the animals are extinct or live much farther south. Many believe man killed off all the animals in the Arctic at the end of the Ice Age, and this produced the wetland. They hope to reclaim the wetland by returning large mammals.

To this end, Pleistocene Park scientists have collected many animals: camels, bison, Yakutian horses, moose, musk oxen, Kalmykian cows, reindeer, sheep, and yaks.5 However, these animals are only intermediate in size, unlike the woolly mammoth. Success in turning local wetland back to grassland has been only modest at best (fig. 1). They are convinced that introducing a mammophant would accelerate the change, since elephants keep trees and bushes from taking over a grassland.

Rewilding won’t bring back the grassland

However, their ideas are overly optimistic, being based on wrong presuppositions.6 For instance, they believe that the animals of Siberia went extinct when man arrived about 10,000–14,000 years ago in the secular timescale. Even within their system of interpretation, this contradicts other evidence that man co-existed with the animals there for some 30,000 years.7 Regardless, it seems highly unlikely that the sparse human population was able to kill off tens of millions of woolly mammoths and many more of the other animals: “It is hard to believe that primitive humans could kill all big herbivores in the high Siberian Arctic”.8 In short, there is little evidence that man caused the mass extinctions.9

In contrast, the biblical Ice Age model has great explanatory power. The warmer oceans for a few centuries after the Flood explain more than just the Ice Age itself. They make sense of why so many animals, many of which currently live in environments less harsh than present-day Siberia, were able to thrive there in the first place. And it also explains why so many disappeared from there or died out entirely after the climate and vegetation changed permanently as the oceans cooled off, ending the Ice Age.10

It is in any case unlikely that large animals would bring back the grassland. Herds of hundreds of thousands of caribou trample across the north in regular migration routes. Yet, wet tundra has not been transformed into a grassland. In fact, the migration path has become even boggier.11

More contrary evidence

A graveyard of about 160 woolly mammoths in Siberia revealed that 42% had destructive bone diseases due to mineral deficiency.12 This is caused by strong acidification of the environment, as occurs in a wetland: “The disease often takes place in acidic landscapes of swamps, taiga, tundra.”13 Diseased animals are also found in many other woolly mammoth graveyards in northern Eurasia.11 Thus, the increase in swamps caused the diseases before the animals died. The change from a grassland to a wetland was not caused by the extinctions; if anything, the extinctions were accelerated by the change.14

This is one more instance where a model based on biblical presuppositions provides better answers, with real-world practical implications.

References and notes

- Fox-Skelly, J., How extinct animals could be brought back from the dead, bbc.com, 16 Jan 2023. Return to text.

- Wilson, J., Cloning a mammoth, Popular Mechanics 177(3):40–41, 2000. Return to text.

- Carter, R., Mammoth clones coming to a zoo near you, Creation 34(2):47, 2012; creation.com/mammoth-clones. Return to text.

- Zimov, S., et al., Mammoth steppe: a high-productivity phenomenon, Quaternary Science Reviews 57:26–45, 2012. Return to text.

- Zimov, S.A., Pleistocene Park: animals, pleistocenepark.ru/animals, acc. 5 Jan 2023. Return to text.

- Oard, M.J., Did megaherbivores create the Ice Age mammoth steppe?, J. Creation (submitted). Return to text.

- Sikora, M., et al., The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene, Nature 570:182–188, 2019. Return to text.

- Zimov, S.A., Pleistocene Park: scientific background, pleistocenepark.ru/science, acc. 5 Jan 2023. Return to text.

- Wang, Y., et al., Late Quaternary dynamics of Arctic biota from ancient environmental genomics, Nature 600:89, 2021. Return to text.

- Oard, M., Over-kill, over-chill, or over-ill? Why a mass extinction at the end of the Ice Age?, Creation 43(1):40–43, 2021; creation.com/kill-chill-ill. Return to text.

- Guthrie, R.D., Origin and causes of the mammoth steppe: a story of cloud cover, woolly mammal tooth pits, buckles, and inside-out Beringia, Quaternary Science Reviews 20:549–574, 2001. Return to text.

- Leshchinskiy, S.V., Strong evidence for dietary mineral imbalance as the cause of osteodystrophy in late glacial woolly mammoths at the Berelyokh site (northern Yakutia, Russia), Quaternary International 445:146–170, 2017. Return to text.

- Leschchinskiy, ref. 12, p. 164. Return to text.

- Davydov, S., et al., Essential mineral nutrients of the high-latitude steppe vegetation and the herbivores of mammoth fauna, Quaternary Science Reviews 228(106073):2, 2020. Return to text.

Readers’ comments

Comments are automatically closed 14 days after publication.